Chapter 1 Introduction to Geology

Adapted from Physical Geology, First University of Saskatchewan Edition (Karla Panchuk) and Physical Geology (Steven Earle)

Figure 1.1: Badlands in southern Saskatchewan. Erosion has exposed layers of rock going back more than 65 million years. Source: Karla Panchuk (2017) CC BY-SA 4.0. Click the image for more attributions.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter and answering the review questions at the end, you should be able to:

- Explain what geology is, and why we study Earth.

- Describe the kinds of work that geologists do.

- Explain what is meant by geological time.

- Explain how the principle of uniformitarianism allows us to translate observations about Earth today into knowledge about how Earth worked in the past.

- Summarize the main idea behind the theory plate tectonics.

1.1 What Is Geology?

Geologists study Earth — its interior and its exterior surface, the rocks and other materials around us, and the processes that formed those materials. They study the changes that have occurred over the vast time-span of Earth’s history, and changes that might take place in the near future.

Geology is a science, meaning that geological questions are investigated with deductive reasoning and scientific methodology. Geology is arguably the most interdisciplinary of all of the sciences because geologists must understand and apply other sciences, including physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, astronomy, and more.

An aspect of geology that is unlike most of the other sciences is the role played by time — deep time — billions of years of it. When geologists study the evidence around them, they are often observing the results of events that took place thousands, millions, and even billions of years in the past, and which may still be ongoing. Many geological processes happen at incredibly slow rates — millimetres per year to centimetres per year — but because of the amount of time available, tiny changes can result in expansive oceans forming, or entire mountain ranges being worn away.

Geology on a Grand Scale in the Canadian Rocky Mountains

The peak on the right of the photographs in Figure 1.2 is Rearguard Mountain, which is a few kilometres northeast of Mount Robson. Mount Robson is the tallest peak in the Canadian Rockies, at 3,954 m. The large glacier in the middle of the photo is the Robson Glacier. The river flowing from Robson Glacier drains into Berg Lake in the bottom right.

Many geological features are shown here. The rocks that these mountains are made of formed in ocean water over 500 million years ago. A few hundred million years later, the rocks were pushed east for tens to hundreds of kilometres, and thousands of meters upward in a great collision between Earth’s tectonic plates.

Over the past two million years this area, like most of the rest of Canada, has been repeatedly covered by glaciers that scoured away rocks to form the valley to the left of Rearguard Mountain. The Robson Glacier itself is now only a fraction of its size during the Little Ice Age of the 15th to 18th centuries. And, like almost all other glaciers on Earth, it is now receding even more rapidly because of climate change. Figure 1.2 (right) taken around 1908 by the Canadian geologist and artist Arthur Philemon Coleman, gives an indication of how much the glacier has receded in the last hundred years.

. Right: A.P. Coleman (c. 1908) Public Domain. Click the image for more attributions._](figures/01-introduction-to-geology/figure-1-2.png)

Figure 1.2: Rearguard Mountain and Robson Glacier in Mount Robson Provincial Park, BC. Left: Robson Glacier today, retreating up the valley. Right: Robson Glacier circa 1908. Sources: Left- Karla Panchuk (2017) CC BY-SA 4.0 with photo by Steven Earle (2015) CC BY 4.0 view source. Right: A.P. Coleman (c. 1908) Public Domain. Click the image for more attributions.

Geology is about understanding the evolution of Earth through time. It is about discovering resources such as metals and energy, and minimizing the environmental implications of our use of resources. It is about learning to mitigate the hazards of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and slope failures. All of these aspects of geology, and many more, are covered in this textbook.

1.2 Why Study Earth?

Why? Because Earth is our home — our only home for the foreseeable future — and in order to ensure that it continues to be a great place to live, we need to understand how it works. Another answer is that some of us can’t help but study it because it’s fascinating. But there is more to it than that.

- Explain what geology is, and why we study Earth.

- Describe the kinds of work that geologists do.

- Explain what is meant by geological time.

- Explain how the principle of uniformitarianism allows us to translate observations about Earth today into knowledge about how Earth worked in the past.

- Summarize the main idea behind the theory plate tectonics.

The Importance of Geological Studies for Minimizing Risks to the Public

Figure 1.3 shows a slope failure that took place in January 2005 in the Riverside Drive area of North Vancouver. The steep bank beneath the house shown gave way, and a slurry of mud and sand flowed down. It destroyed another house below, and killed one person. The slope failure happened after a heavy rainfall, which is a common occurrence in southwestern B.C. in the winter.

Figure 1.3: Aftermath of a deadly debris flow in the Riverside Drive area of North Vancouver in January, 2005. Source: The Province (2005), used with permission.

A geological report written in 1980 warned the District of North Vancouver that the area was prone to slope failure, and that steps should be taken to minimize the risk to residents. Unfortunately, not enough was done in the intervening 25 years to prevent a tragedy.

1.3 What Do Geologists Do?

Geologists do a lot of different things. Many of the jobs are the things you would expect. Geologists work in the resource industry, including mineral exploration and mining, and exploring for and extracting sources of energy. They do hazard assessment and mitigation (e.g., assessment of risks from slope failures, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions). They study the nature of the subsurface for construction projects such as highways, tunnels, and bridges. They use information about the subsurface for water supply planning, development, and management; and to decide how best to contain contaminants from waste.

Geologists also do the research that makes practical applications of geology possible. Some geologists spend their summers trekking through the wilderness to make maps of the rocks in a particular location, and collect clues about the geological processes that occurred there. Some geologists work in laboratories analyzing the chemical and physical properties of rocks to understand how the rocks will behave when forces act on them, or when water flows through them. Some geologists specialize in inventing ways to use complex instruments to make these measurements. Geologists study fossils to understand ancient animals and environments, and go to extreme environments to understand how life might have originated on Earth. Some geologists help NASA understand the data they receive from objects in space.

Geological work can be done indoors in offices and labs, but some people are attracted to geology because they like to be outdoors. Many geological opportunities involve fieldwork in places that are as amazing to see as they are interesting to study. Sometimes these are locations where few people have ever set foot, and where few ever will again.

_](figures/01-introduction-to-geology/figure-1-4.jpg)

Figure 1.4: Geologists at work on the island of Spitsbergen, part of the Svalbard archipelago. The islands are located in the Arctic Ocean north of Norway. Source: Gus MacLeod (2007) CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 view source

1.4 We Study Earth Using the Scientific Method

There is no single method of inquiry that is specifically the scientific method. Furthermore, scientific inquiry is not necessarily different from serious research in other disciplines. The key features of serious inquiry are the following:

- Explain what geology is, and why we study Earth.

- Describe the kinds of work that geologists do.

- Explain what is meant by geological time.

- Explain how the principle of uniformitarianism allows us to translate observations about Earth today into knowledge about how Earth worked in the past.

- Summarize the main idea behind the theory plate tectonics.

1.4.1 An Example of the Scientific Method at Work

Consider a field trip to the stream shown in Figure 1.5 Notice that the rocks in and along the stream are rounded off rather than having sharp edges. We might hypothesize that the rocks were rounded because as the stream carried them, they crashed into each other and pieces broke off.

_](figures/01-introduction-to-geology/figure-1-5.jpg)

Figure 1.5: Hypothesizing about the origin of round rocks in a stream. Source: Steven Earle (2015) CC BY 4.0 view source

If the hypothesis is correct, then the further we go downstream, the rounder and smaller the rocks should be. Going upstream we should find that the rocks are more angular and larger. If we were patient we could also test the hypothesis by marking specific rocks and then checking back to see if those rocks have become smaller and more rounded as they moved downstream.

If the predictions turn out to be correct, we must still be careful about how much certainty to attach to our hypothesis. Although our hypothesis might seem to us to be the only reasonable explanation, someone could argue that we have the mechanism wrong, and the rocks weren’t rounded by bumping into each other. If our experiment didn’t specifically check for the mechanism (e.g., by looking to see if chips fall off the rocks and the rocks are made smoother) then we would have to acknowledge the possibility. We needn’t abandon the hypothesis as a useful tool for making predictions, but it is necessary to be open to the possibility that other things might be going on. If someone demonstrates conclusively that our hypothesis is wrong, then we have to discard the hypothesis and come up with a better one.

A good hypothesis is testable. Someone might argue that an extraterrestrial organization creates rounded rocks and places them in streams when nobody is looking. There is no practical way to test this hypothesis to confirm it, and there is no way to prove it false. Even if we never see aliens at work, we still can’t say they haven’t been, because according to the hypothesis they only work when people aren’t looking. Compare this to our original hypothesis which allows us to make testable predictions such as rocks getting smaller and rounder downstream. Our original hypothesis gives us a way to see how realistic it is, whereas the alien hypothesis gives us no way to know if it makes sense or not.

1.4.2 Theories and Laws

Two other terms appear in discussions of the scientific method: theory and law. A theory starts out as a hypothesis, but over a long period of time and a great many tests, it has never come up short. That doesn’t mean it never will, but the odds of that are very unlikely given our present (and conceivable future) state of knowledge. You may have heard someone dismiss an idea by saying it is “just a theory,” but they are using the term incorrectly if they mean to say it’s a wild and unproven guess.

A law is a description of a phenomenon rather than an explanation of it. For example, you could do thousands of tests by dropping an object with known mass and measuring its acceleration and the force with which it hits the ground. Again and again your results will yield the formula force = mass x acceleration. However, that doesn’t mean you know what is responsible for the force accelerating it toward the ground. Yes, we say that gravity is pulling it toward the Earth’s surface, but why? A law is true regardless of why a phenomenon happens as long as it describes the outcome of that phenomenon.

1.5 Three Big Ideas: Geological Time, Uniformitarianism, and Plate Tectonics

In geology there are three big ideas that are fundamental to the way we think about how Earth works. The ideas are like the sound track to a movie- sometimes we might not even notice them, but at the same time they affect our perception of what is happening. In the rest of this book these ideas may be mentioned explicitly in some cases, but in other cases it will be helpful for you to realize that they are relevant, even if they are not being discussed by name.

1.5.1 Geological Time (Deep Time)

Earth is approximately 4.57 billion years old (4,570,000,000 years), which is a long time for geological events to unfold and changes to happen. The changes themselves might be tiny. For example, over a year, a chemical reaction might eat away a few layers of atoms at the surface of a rock. But over time the changes accumulate and have a great impact. Over hundreds of millions of years the chemical reaction could cause a mountain range to crumble into grains of sand, and be swept away by rivers.

For geologists who study very, very slow processes, 10 million years might be a short time, and 1 million years might be trivial. For these geologists, intervals of 1 million years aren’t even useful to consider, because the changes over that time are too small to see in the rocks that accumulated.

As you read through this book, keep in mind that the well of geologic time is indeed deep, and “ancient” is defined in a whole new way.

1.5.1.1 Expressing Geological Time in Numbers

Special notation is used for geological time because, as you might imagine, writing all those zeroes can become tiresome. Table 1.1 shows common abbreviations you will see throughout this book.

| Abbreviation | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ga | giga annum or billions of years | Earth is 4.57 Ga old. |

| Ma | mega annum or millions of years | Earth is 4,570 Ma old. |

| ka | kilo annum or thousands of years | The last glacial cycle ended 11,700 years ago, or 11.7 ka. |

1.5.1.2 Expressing Geological Time Using the Geological Time Scale

The geological time scale (Figure 1.6) is a way of breaking down geological time according to important events in Earth’s history. Time is divided into eons, eras, periods, and epochs, and these intervals are referred to by names rather than by years. Giving intervals of geologic time names rather than using numbers makes sense because we won’t always know the age in years (the absolute age) of a rock or fossil, but we can place it in context based on our knowledge of the geological record. We can describe its relative age by saying that it is older than or younger than another rock or fossil.

_](figures/01-introduction-to-geology/figure-1-6.png)

Figure 1.6: Geologic Society of America Geologic Time Scale, 2012. Source: Walker, J.D., Geissman, J.W., Bowring, S.A., and Babcock, L.E., compilers (2012) Geologic Time Scale v. 4.0: Geological Society of America, doi: 10.1130/2012.CTS004R3C. Download PDF

The tricky thing about the geologic time scale is that the boundaries are always changing. As our knowledge of the absolute age of an event improves with new discoveries, it might be necessary to nudge a boundary earlier or later. Sometimes the original reason for defining a boundary no longer holds, but we agree to use it anyway. For example, the Phanerozoic Eon (the last 542 million years) is named for the time during which visible (phaneros) life (zoi) is present in the geological record, and its start was meant to mark the first appearance of these organisms. In fact, we now have evidence that large organisms — those that leave fossils visible to the naked eye — have existed longer than that, first appearing by 600 Ma at the latest.

An Early Definition of the Proterozoic

Notice that in Figure 1.6 the Proterozoic Eon precedes the Phanerozoic Eon. This was not always the case. Figure 1.7 shows an excerpt from a periodical published in 1879, in which the Proterozoic is defined as covering the Cambrian through Silurian. The author refers to “the most extreme adherents of the Murchisonian party in geology,” a reference to the contentious assertion by Scottish geologist Roderick Murchison (1792-1871) that the Silurian Period should encompass the Cambrian and Ordovician periods as well.

_](figures/01-introduction-to-geology/figure-1-7.png)

Figure 1.7: An excerpt from the periodical The Annals and Magazine of Natural History (1879) in which the name “Proterozoic” is assigned to the Cambrian, Ordovician, and Silurian periods instead of to the time preceding the Cambrian. Source: Karla Panchuk (2017) CC BY 4.0 Read the book

1.5.1.3 A Way To Think About Geological Time

A useful mechanism for understanding geological time is to scale it down into one year. The origin of the solar system and Earth at 4.57 Ga would be represented by January 1, and the present year would be represented by the last tiny fraction of a second on New Year’s Eve. At this scale, each day of the year represents 12.5 million years; each hour represents about 500,000 years; each minute represents 8,694 years; and each second represents 145 years. Some significant events in Earth’s history, as expressed on this time scale, are summarized in Table 1.2.

| Event | Approximate Date | Calendar Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Formation of oceans and continents | 4.5 - 4.4 Ga | first week of January |

| Evolution of the first primitive life forms | 3.8 Ga | end of February |

| Formation of Saskatchewan’s oldest rocks | 3.4 Ga | end of March |

| Evolution of the first multi-celled animals | 600 Ma | beginning of November |

| Animals first crawled onto land | 360 Ma | end of November |

| Vancouver Island reached North America and the Rocky Mountains were formed | 90 Ma | December 16 |

| Extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs | 65 Ma | December 18 |

| Beginning of the Pleistocene ice age | 2 Ma | 10:10 p.m., December 31 |

| Oldest radiocarbon date from people living in Canada (British Columbia) | 13.8 ka | 11:58 p.m., December 31 |

| Earliest evidence of human activity in Saskatchewan | 11.5 ka | 48 seconds before midnight, December 31 |

| The last of the glacial ice retreats from Saskatchewan | 6 ka | 41 seconds before midnight, December 31 |

| Hudson’s Bay Company establishes a permanent settlement at Cumberland House in northern Saskatchewan | 243 years ago | 2 seconds before midnight, December 31 |

1.5.2 Uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism is the notion that the geological processes occurring on Earth today are the same ones that occurred in the past. This is an important idea because it means that observations we make today about geological processes can be used to interpret and understand the rock record. While this idea might not seem remarkable today, it was ground breaking and even controversial for its time. Many people who heard about it for the first time thought about the age of the Earth in thousands of years, but uniformitarianism required them to think on timescales almost too vast to comprehend. For some, this implied questioning their most deeply held religious beliefs.

The Scottish geologist James Hutton initially presented the idea in 17851. Charles Lyell, also a Scottish geologist, paraphrased this idea as “the present is the key to the past” in his book Principles of Geology.2 This is how it is often described today.

To be clear, “the present is the key to the past” can be viewed as an oversimplification. Not all geological processes occurring today occurred at all times in the geological past. For example, some important chemical reactions that happened on Earth’s surface today require abundant oxygen in the atmosphere, and could not have occurred prior to Earth developing an oxygen-rich atmosphere. Conversely, there was a time in Earth’s history when continents as we know them hadn’t yet developed. Some events, such as devastating impacts by objects from space, have never been witnessed on the same scale by humans. We must be cognizant of the fact that conditions were different at different times in Earth’s history, and take that into account when interpreting the rock record.

Despite the different past conditions on Earth as a whole, there still exist environments today where some of these conditions are present. These environments are like little samples of what Earth used to be like. This means we can still use present conditions to inform us about the past, but we have to think carefully about ways that such environments today differ from the ancient environments that no longer exist.

1.5.3 Plate Tectonics

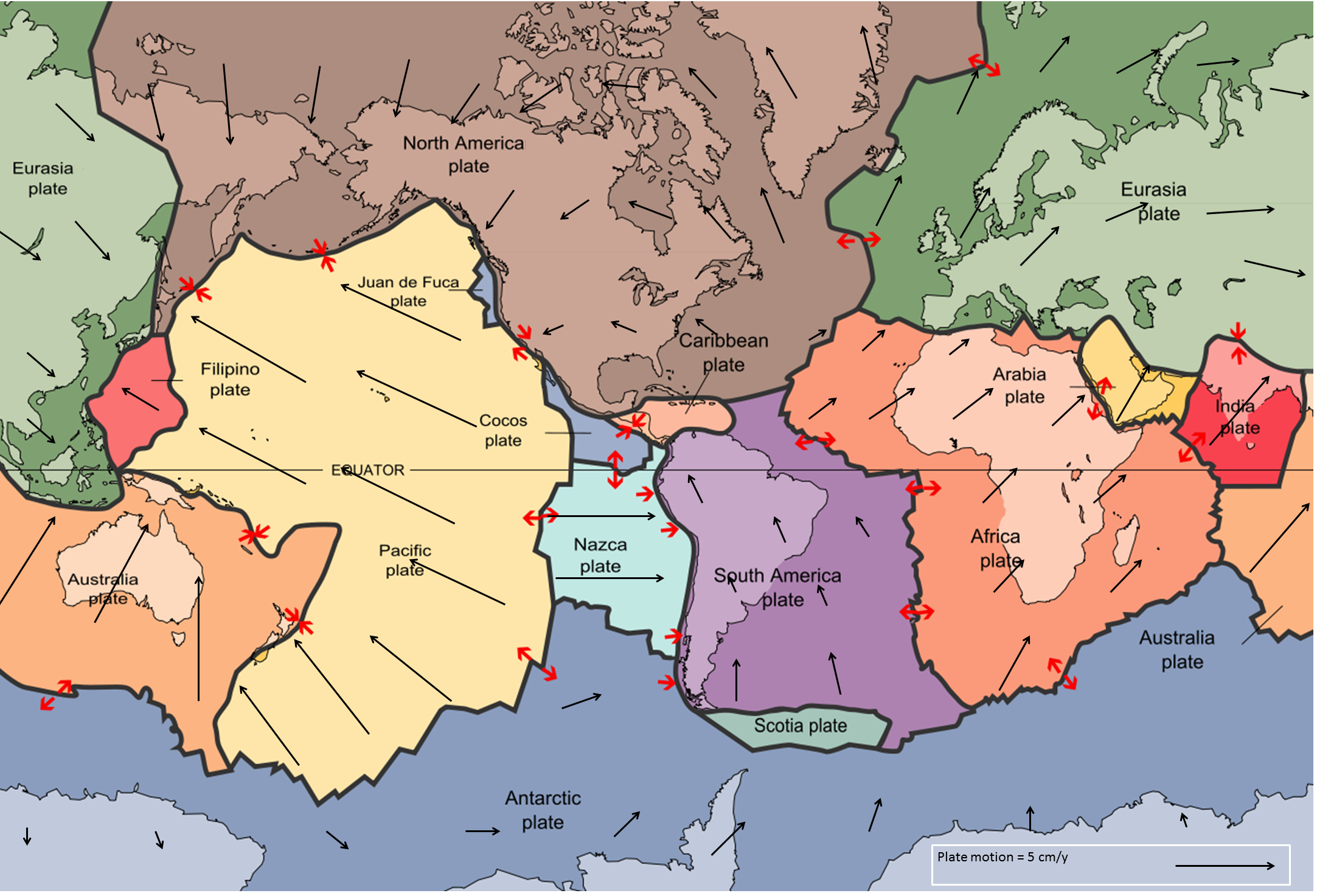

It is only within the last 50 years or so that we have been able to answer questions like, “How did that mountain range get there?” and “Why do earthquakes happen where they do?” The theory of plate tectonics- the idea that Earth’s surface is broken into large moving fragments, called plates- profoundly changed our perspective on how the Earth works. Figure 1.8 shows Earth’s 15 largest tectonic plates, along with arrows indicating the plates’ direction of motion, and how fast they go. (Longer arrows mean faster motion.) There are many more plates on Earth that are too small to show conveniently in Figure 1.8. A more detailed map of Earth’s tectonic plates can be found at here.

Modified after U. S. Geological Survey (1996) Public Domain [view original](https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/slabs.html)_](figures/01-introduction-to-geology/figure-1-8.png)

Figure 1.8: Earth’s fifteen largest tectonic plates. Black arrows show the direction of plate motions. The length of the arrow indicates velocity. Red arrows show how plates move relative to each other. Source: Steven Earle (2015) CC BY 4.0. view source Modified after U. S. Geological Survey (1996) Public Domain view original

Prior to plate tectonics, we made observations but could only guess at mechanisms. It was like watching the hands on a clock and trying to guess what moves them. After plate tectonics it was like being able to open the clock and not only watch the gears turn, but realize for the first time that there are such things as gears. Plate tectonics not only explains why things have happened, but also allows us to predict what might happen in the future.

Plate tectonics is covered in more detail later, however the key point is that Earth’s outer layer consists of rigid plates that are constantly interacting with each other as they move around the Earth. The boundaries of plates move away from each other in some places, collide in others, and sometimes just slide past each other (illustrated by the red arrows in Figure 1.8). The plates can move because they are floating on a layer of weak rock that deforms as the plates travel, much the same way the filling in a peanut butter and jelly sandwich allows you to slide the top layer of bread across the bottom layer.

Whether the plates move away from each other, collide, or just slide past each other determines things like the locations of mountain belts and volcanoes, where earthquakes happen, and the shapes and sizes of oceans and continents.

1.6 Summary

The topics covered in this chapter can be summarized as follows:

1.6.1 What is Geology?

Geology is the study of Earth. It is an integrated science that involves the application of many of the other sciences. Geologists must take into account the fact that the geological features we see today may have formed thousands, millions, or even billions of years ago, and over very long time spans.

1.6.2 Why Study Earth?

Geologists study Earth out of curiosity and for other, more practical reasons, including understanding the evolution of life on Earth; searching for resources; understanding risks from geological events such as earthquakes, volcanoes, and slope failures; and documenting past environmental and climate changes so that we can understand how human activities are affecting Earth.

1.6.3 What Do Geologists Do?

Geologists work in the resource industry, and in efforts to protect the environment. Geologists work to minimize the risks from geological hazards (e.g., earthquakes), and to help the public understand those risks. Geologists investigate Earth materials in the field, in and in the lab.

1.6.4 We Study Earth Using the Scientific Method

Scientific inquiry requires a careful process of making a hypothesis and then testing it. If a hypothesis doesn’t pass the test, it’s time for a new one. A theory is a hypothesis that has been tested repeatedly and never failed a test. A law is a description of a natural process.

1.6.5 Three Big Ideas: Geological Time, Uniformitarianism, and Plate Tectonics

Geological time: Earth is approximately 4,570,000,000 years old; that is, 4.57 billion years or 4.57 Ga or 4,570 Ma. It’s such a huge amount of time that even extremely slow geological processes can have an enormous impact.

Uniformitarianism: Processes that occur today also occurred in the geologic past. We can use our observations of the present to understand the processes that shaped the Earth throughout its history.

Plate tectonics: Earth’s surface is broken into plates that move and interact with each other. The interactions between these plates are key for understanding the mechanisms behind geologic processes.

1.7 Chapter Review Questions

How does the element of time make geology different from the other sciences, such as chemistry and physics?

List three ways in which geologists can contribute to society.

The following dates are written with the abbreviations Ga, Ma, and ka. Express the dates in years. (For example, 2.3 Ma = 2,300,000 years)

- 2.75 ka

- 0.93 Ga

- 4.2 Ma

- 0.2 ka

Dinosaurs first appear in the geological record in rocks from about 215 Ma and then most became extinct at 65 Ma. What percentage of geological time does this represent?

If sediments typically accumulate at a rate of 1 mm/year, what thickness of sediment could accumulate over a period of 30 million years?

Does uniformitarianism mean that conditions on Earth are uniform, and never change?

Summarize the main idea behind plate tectonics.

1.8 Answers to Chapter Review Questions

Geology requires that we consider vast amounts of time, and think about the effects that accumulate over thousands, millions, or even billions of years.

There are many ways that geologists contribute. Geologists provide information to reduce the risk of harm from hazards such as earthquakes, volcanoes, and slope failures; they play a critical role in the discovery of important resources; they contribute to our understanding of life and its evolution through paleontological studies; and they play a leading role in the investigation of climate change, past and present and its implications.

Ages in years:

- 2.75 ka = 2,750 years

- 0.93 Ga = 930,000,000 years

- 14.2 Ma = 14,200,000 years

- 0.2 ka = 200 years

215 - 65 = 150 Ma. Since the age of the Earth is 4570 Ma, this represents 150/4,570 = 0.033 or 3.3% of geological time.

At 1 mm/y 30,000,000 mm of sediment would accumulate over that 30 million years. This is equivalent to 30,000 m or 30 km. Few sequences of sedimentary rock are even close to that thickness because most sediments accumulate at much lower rates, more like 0.1 mm/y. Also, over time the sediments are compressed.

No. Uniformitarianism means that we can use the processes we observe today to help us understand what happened in the past.

Plate tectonics is the idea that Earth’s outer layer is broken into rigid plates. The plates move around and interact with each other along their margins.

1.9 References

Cottrell, M. (2006) History of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 26 August 2017. Visit the website

Victoria University Library (2009) A. P. Coleman Exhibition. Retrieved 25 August 2017. Visit the website

Read James Hutton’s abstract at http://bit.ly/1j6tIAN. Note that the typeface prints an “s” like an “f.”↩︎

The 7th edition of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1847) can be found at http://bit.ly/1l3T6Zh↩︎